Please provide your information and submit this form. Our team will be in touch with you shortly.

0 out of 18

0 out of 18

What is the purpose of estate management? Estate management is about preserving the assets you’ve spent a lifetime building. It’s about protecting your spouse, children, or other heirs and ensuring that your assets are distributed how and when you want them to be. Finally, estate management is about managing the amount of estate taxes that may be due after your death. There are some fundamental estate management principles that can enable you to manage your financial and personal affairs during your lifetime and distribute your wealth after death.

There are two objectives in effective estate management:

First, managing your financial and personal affairs during your lifetime;

And second, distributing your wealth after your death.

Done well, estate management can make a huge difference. It can enable you to spell out your healthcare wishes in ways that may help ensure they are carried out—even if you are unable to communicate. And it can help ensure that your possessions go to the heirs you choose, without the endless legal wrangling that can tie up your estate and cause deep divisions within your family. Through effective estate management you can avoid needless expense in legal costs, and you can provide for loved ones who may not be protected otherwise. These issues are too important to trust to luck—you need to determine the outcome by planning in advance.

We’ve found it helpful to illustrate the various estate management principles and strategies as a pyramid. The foundation is formed by an understanding of how estate taxes work. As we move up, we encounter critical estate management documents and, at the top, specific tactics for estate management.

Let’s begin by discussing the foundation of our estate pyramid: how estate taxes work

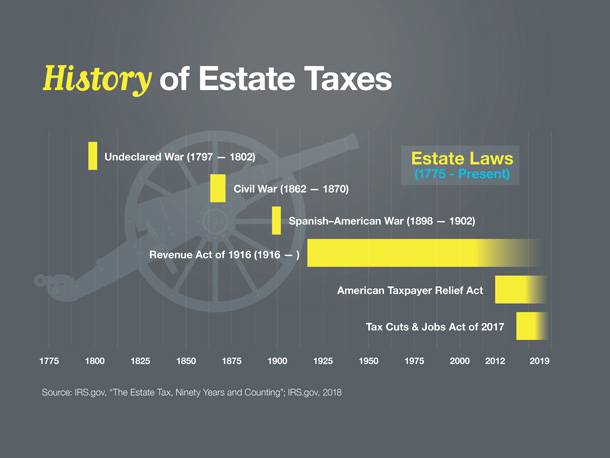

In order to understand how estate taxes work, let’s look at the history of the estate tax. The first estate tax was established in 1797 to fund an undeclared naval war with France. Shortly after the war ended, the tax went away.

That happened again for the Civil and Spanish-American wars. Congress passed an estate tax to pay for the war, then repealed it afterward.

Until 1916. The 16th Amendment to the Constitution was passed in 1913—the one that gives Congress the right to “lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived.” The Revenue Act of 1916 established estate tax; it’s been modified over the years but never repealed.

In 2012, the American Tax Relief Act made the estate tax a permanent part of the tax code.

In 2017, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act doubled the estate tax exemption to $11.2 million. That law is currently set to expire December 31, 2025.

Source: IRS.gov, “The Estate Tax, Ninety Years and Counting”; IRS.gov, 2018

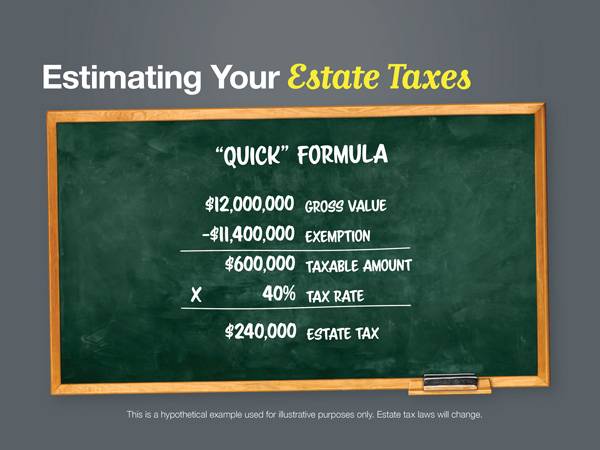

This hypothetical example shows the formula for estimating estate taxes is actually quite simple.

If you don’t happen to have a complete set of IRS tax tables lying about, you can estimate the federal estate tax by using a quick formula. Beginning with the gross value of an estate, subtract the exemption amount of $11,400,000. Then multiply the result by 40%—the federal tax bracket for estates above $11,400,000 in size.

If you complete your estimation—and find you may have an estate tax bill—it’s possible you may benefit from estate management.

There are a number of critical documents you may need to have as part of your estate plan. The first of these is a will. A will is the most basic estate planning document. A will tells the world exactly where you want your assets distributed when you die.

Everyone should have a will, but according to one study, roughly 60% of Americans don’t have one.

That’s really short-sighted—and not just for the wealthy—because if an individual dies intestate, or without a will, it’s up to the state to decide how his or her assets will be distributed.

Even if you have a trust, you still need a will to take care of any holdings outside of that trust when you die.

Source: CNBC.com, August 22, 2018

A will is really the cornerstone of your estate.

Your will names an executor to oversee the process of distributing your estate. It can name a guardian for your minor children. And it can direct how your property is to be distributed.

Unfortunately, as important as they are, wills have shortcomings.

Wills can be contested. In fact, the probate court will send out notice of the will to anyone who might have grounds to contest it. And if someone wants to contest it, there is the potential for a lengthy battle in probate court.

Since wills are essentially instructions to the probate court, they pretty much guarantee probate. The probate process can be expensive, and it can take many months or more than a year to resolve.

And probate is a matter of public record.

If the only estate management tool you use is a will, anyone who wants to can find out how much you left and to whom.

We’ll talk more about how you can potentially avoid probate and distribute your assets to your heirs privately. But first, there are some essential documents that most people should consider having in place.

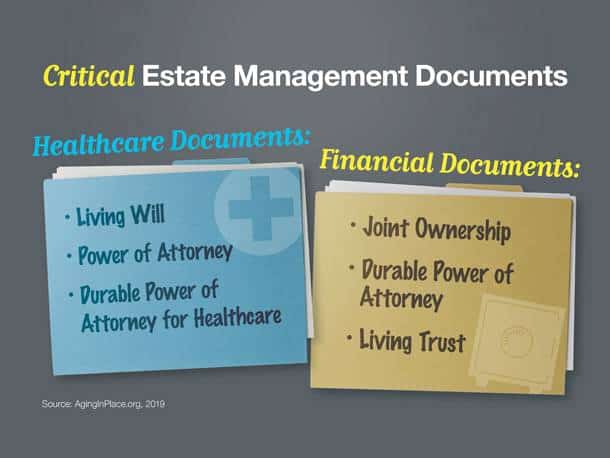

To really take care of your estate, a will isn’t the only document you need to have in place. There is actually a whole set of documents that can help you pursue your estate management goals.

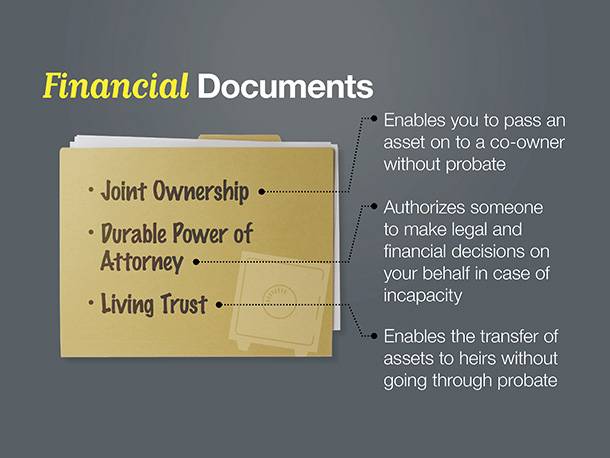

Among these are “advanced directives,” which include a living will, power of attorney, and the durable power of attorney for healthcare. There are also financial documents and agreements like joint ownership, durable power of attorney, and living trusts.

Back in 2006, the case of Terry Schiavo brought advance directives to the forefront. As you may remember, Ms. Schiavo was severely incapacitated, and her family members battled for years about what should be done. Since Ms. Schiavo did not have a living will, her wishes could not be known. In spite of the high-profile nature of that case, most Americans still do not have their healthcare documents prepared and have not had a conversation with loved ones about what level of care they want if they are incapacitated.

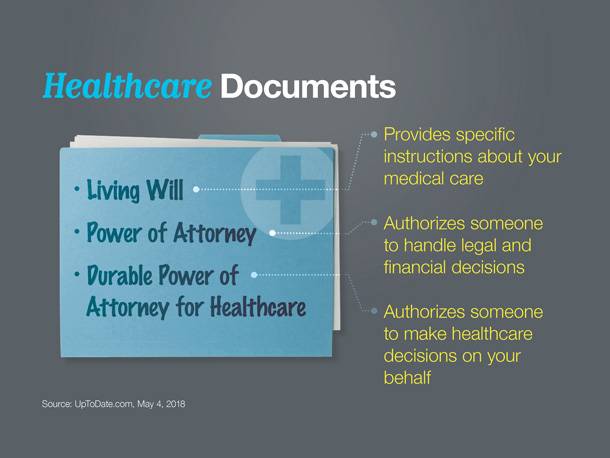

A living will provides specific instructions about your medical care if you become incapacitated and unable to communicate. It goes into effect immediately upon your incapacity and doesn’t need to go through any additional legal proceedings.

A power of attorney document authorizes someone to handle legal and financial decisions when you become incapacitated. It can also go into effect upon your incapacity, or upon any other trigger event you specify. Like a living will, a power of attorney does not need to go through any additional legal proceedings. Individual states can have various power of attorney laws. So consider becoming familiar with your state’s particular regulations in order to make a more informed decision.

A durable power of attorney for healthcare agreement authorizes someone to make decisions for healthcare on your behalf. And, like the living will and the power of attorney, it does not need to go through any additional legal proceedings.

Source: AgingInPlace.org, 2019

Considering the case of Terry Schiavo, would your family know your wishes if you became incapacitated?

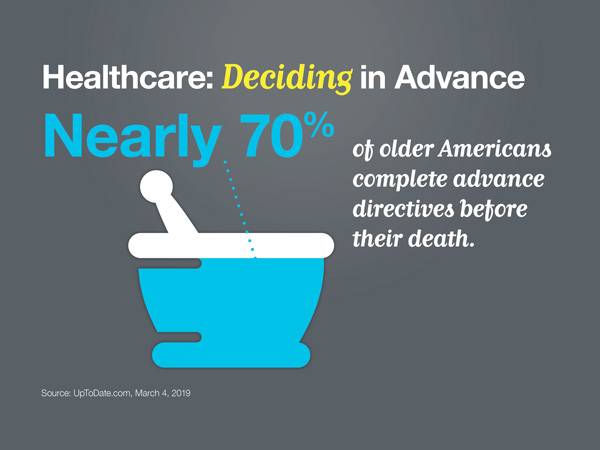

Contemporary research shows that about 70% of older Americans complete advance directives before their death. That’s up from 30% only a decade ago.

With extended life expectancy and a variety of treatment options available, the chance that you or someone close to you will benefit from an advance directive is greater than ever.

Source: UpToDate.com, May 4, 2018

Just as there are certain essential documents regarding healthcare, there are some critical financial documents in effective estate management.

Joint ownership is actually a way of holding title to property. It’s useful because if one of the partners dies, the other can assume ownership without the property having to go through probate. It goes into effect as soon as joint ownership is recorded and it does not need to go through any additional legal proceedings.

A durable power of attorney allows you to appoint a person or organization to take care of your financial affairs when you are unable to do so. It is “durable” because it includes specific language that allows it to remain in effect or to take effect if you become mentally incompetent. It can go into effect immediately or when a specific trigger event occurs—such as your incapacity. Powers of attorney can be rescinded at any time and do not need to go through any additional legal proceedings.

A living trust is a trust created while you are still alive. Living trusts go into effect when the trust documents are signed and the trust is funded — that is, when you’ve transferred assets into it. Living trusts do not need to go through any additional legal proceedings.

Of course, estate management isn’t all documents. There are some basic tactics to understand as well.

The first of these is simple: give money away while you’re still alive.

The tax code allows an individual to gift up to $15,000 per person in 2019 without triggering any gift or estate taxes. If you and your spouse both make gifts, that’s up to $30,000 in 2019. However, if a person gives $16,000 to someone, the person must pay gift tax on the remaining $1,000. The annual exclusion amount is indexed for inflation, which is measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). It rises in $1,000 increments as the CPI increases.

In 2019, an individual can give away up to $11,400,000 during his or her lifetime without owing any federal tax. Couples can leave up to twice that without owing any federal tax. Also, keep in mind that some states may have their own estate tax regulations.

Source: Internal Revenue Service, 2019

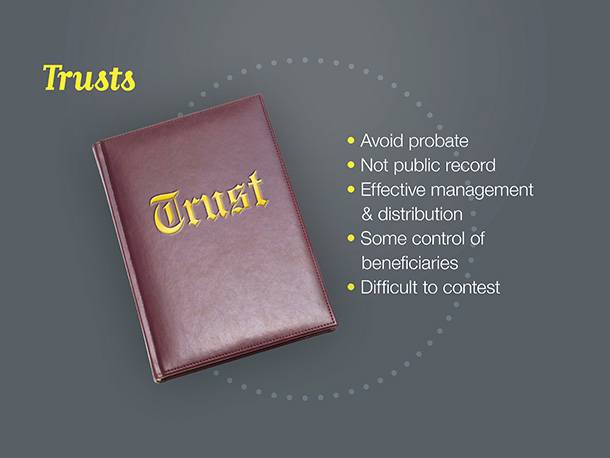

Trusts can be another powerful estate management tool.

A trust is a legal entity that can own property. Properly structured trusts completely avoid probate and avoid the delays and expense that often accompany probate. Trusts are not a matter of public record. They’re a tool for maintaining privacy.

Trusts can provide very effective management of your assets and their distribution to your heirs.

And, even after your death, trusts can provide some measure of control over how assets are distributed to children and other beneficiaries. In addition, trusts are much more difficult to contest than a will.

Using a trust involves a complex set of tax rules and regulations. Before moving forward with a trust, consider working with a professional who is familiar with the rules and regulations.

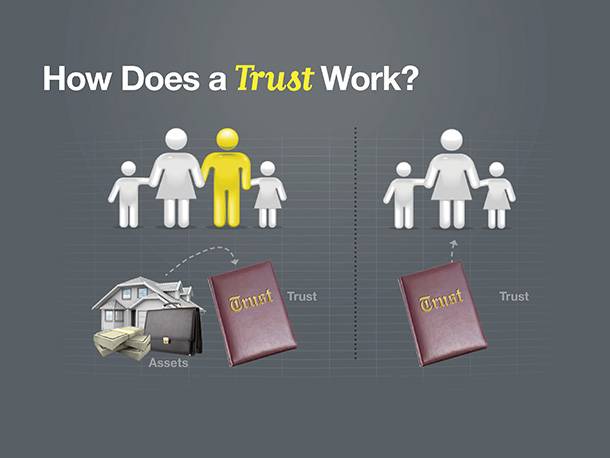

How does a trust work?

First, you establish a trust. Then you transfer ownership of some or all of your property to the trust. That makes you the grantor—the one who “grants” the assets. Your new trust will then be managed by a trustee. And since you can make yourself the trustee, you don’t actually give up any control over the property you put in the trust.

In the trust document, you name those you want to inherit everything in the trust upon your death. You can change those choices if you wish; you can revoke the trust at any time.

When you die, the person you named in the trust document to take over—called the successor trustee—transfers ownership of everything in the trust to the people you want to get it. In most cases, the whole process can be handled quickly with some simple paperwork. And nothing has to go through the delays or expense of probate.

There are several types of trusts to answer different estate challenges. It’s important to work with a professional to find the right trust vehicle; one that will protect your loved ones when you are no longer there to make financial decisions.

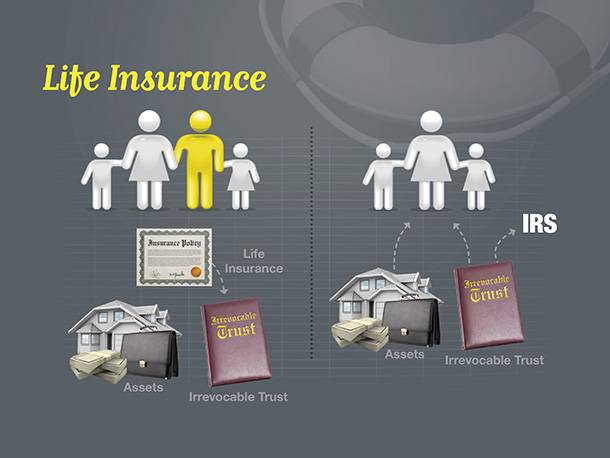

Life insurance also can play a critical role in your estate management—particularly when used in conjunction with a trust.

Life insurance can provide money to pay for estate expenses. It can be set up outside your estate. You can even gift life insurance policies.

That makes it a very powerful tool. Let’s look at just one example:

Under this strategy, a person establishes an irrevocable trust and funds it. The trust then purchases a life insurance policy on the life of the person that established it. This effectively removes the life insurance policy—and its eventual benefit—from the person’s estate.

Then, when the person dies, the estate passes to his or her heirs, and the life insurance policy provides the funds to pay any estate taxes that come due.

Several factors will affect the cost and availability of life insurance, including age, health, and the type and amount of insurance purchased. Life insurance policies have expenses, including mortality and other charges. If a policy is surrendered prematurely, the policy holder also may pay surrender charges and have income tax implications. You should consider determining whether you are insurable before implementing a strategy involving life insurance. Any guarantees associated with a policy are dependent on the ability of the issuing insurance company to continue making claim payments. Life insurance is not insured by any federal government agency or bank or savings association.

What do you need to consider when putting together a management plan for your estate?

There are two crucial factors to consider:

First, what’s the value of your estate? As you make this calculation, make sure you include all the property that you control or have an interest in. This includes personal property, your home, real estate, cash and bank accounts, investments, retirement plans, business interests, and life insurance—including the death benefits. In 2019, the gross value of your estate must exceed $11,400,000 in order for you to be subject to the federal estate tax. But even if you are not, you should consider getting your estate and healthcare documents in order so that your wishes may be carried out.

Second, what are your estate management objectives? Ask yourself the following questions: Whom do you want to inherit your assets? Whom do you want handling your financial affairs if you’re ever incapacitated? Whom do you want making medical decisions for you if you become unable to make them for yourself? Do you want to provide for your spouse if you should die first? Do you have young children to provide for? If your children are grown, do you want to distribute your estate equitably—if not perfectly equally? Will you need to provide cash to help your heirs settle your estate?

Principles of estate management are important for many reasons. Here are some scenarios that may be familiar:

Anthony and Selena, a couple with children, ask, “What is the best way to gift assets to our children and grandchildren? We have a blended family. What type of trust would be appropriate for us?”

Dave and Christine, a retired couple, want to know: “Is a living trust worth the trouble and expense to set up? What is the best way for us to take title of our assets?”

Rebecca, a single parent and business owner, wonders: “How shall I protect my business interests in the event of my passing? Do I have all of the critical documents I need in case of a catastrophic change in my health?”

Isaac likes to do research online. He asks: “Are the critical healthcare documents I downloaded legally binding? How can I make sure I avoid probate and estate taxes.”

The answers to these and other concerns will vary with each individual situation and can all be addressed in a review.